The Colditz Cock: A Detailed Account of Ingenuity During Wartime

- dthholland

- Oct 6, 2024

- 5 min read

The Colditz Cock, a glider constructed by Allied prisoners of war (POWs) held at Colditz Castle during the Second World War, represents an extraordinary example of wartime engineering. However, the glider was never flown. The project did not stem from a clear intent to escape but served primarily as a means of maintaining morale and occupying the minds of the prisoners as the war approached its final stages.

Background: The Great Escape and Its Aftermath

By the time the Colditz Cock project began, the atmosphere among Allied POWs in German camps had shifted markedly following the events of the “Great Escape” in March 1944. During this operation, 76 prisoners managed to escape from Stalag Luft III, a camp for Allied airmen. In the wake of this large-scale breakout, Adolf Hitler ordered that 50 of the recaptured escapees be executed as a deterrent to future attempts. The heavy loss of life led the Allied High Command to discourage future escape efforts, especially those involving large numbers of prisoners.

Nevertheless, in Colditz Castle—one of the most secure POW camps, reserved for those who had repeatedly attempted to escape from other camps—there remained a spirit of defiance. Rather than purely suppressing escape attempts, the camp authorities at Colditz Castle tacitly encouraged activities that might divert the prisoners’ attention from the monotony of captivity. This environment allowed the glider project to take root, although its aim became more symbolic than practical as the war progressed.

The Genesis of the Glider Plan

The idea of building a glider to escape Colditz originated with Lieutenant Tony Rolt, a British Army officer. Unlike many of his fellow prisoners, Rolt was not an airman. However, he noticed something that others had overlooked—the roofline of the chapel at Colditz Castle was not visible to the German guards. Positioned high on a ridge overlooking the River Mulde, the castle’s architecture presented an opportunity that had gone unexploited. From this concealed vantage point, a small glider could theoretically be launched across the river, potentially enabling a pair of prisoners to escape.

Rolt’s observation provided the basis for what became known as the Colditz Cock project, though it should be noted that Rolt himself did not actively participate in the construction. The practical execution of the plan was entrusted to a group of prisoners with experience in engineering and aircraft design.

Construction Begins: Leadership and Expertise

The glider’s construction was led by two Royal Air Force (RAF) officers, Bill Goldfinch and Jack Best. Both men had engineering backgrounds, and their expertise proved critical to the project. They were aided by a valuable resource in the prison library: Aircraft Design, a two-volume book by C.H. Latimer-Needham. This technical manual contained detailed information on the principles of aerodynamics, wing structure, and aircraft construction, which proved indispensable. Goldfinch and Best, with a group of twelve assistants, began work on the glider in late 1944.

The construction took place in a concealed attic space above the chapel. To ensure secrecy, the team built a false wall to hide their activities from the German guards. Although German security measures in Colditz were notoriously stringent, the focus was primarily on preventing tunnelling attempts. As a result, the Germans paid little attention to the attic, and the glider builders were able to work with relative freedom. Nevertheless, the prisoners remained cautious, setting up lookouts and an electric alarm system to alert them if guards approached the workshop.

Materials and Construction Challenges

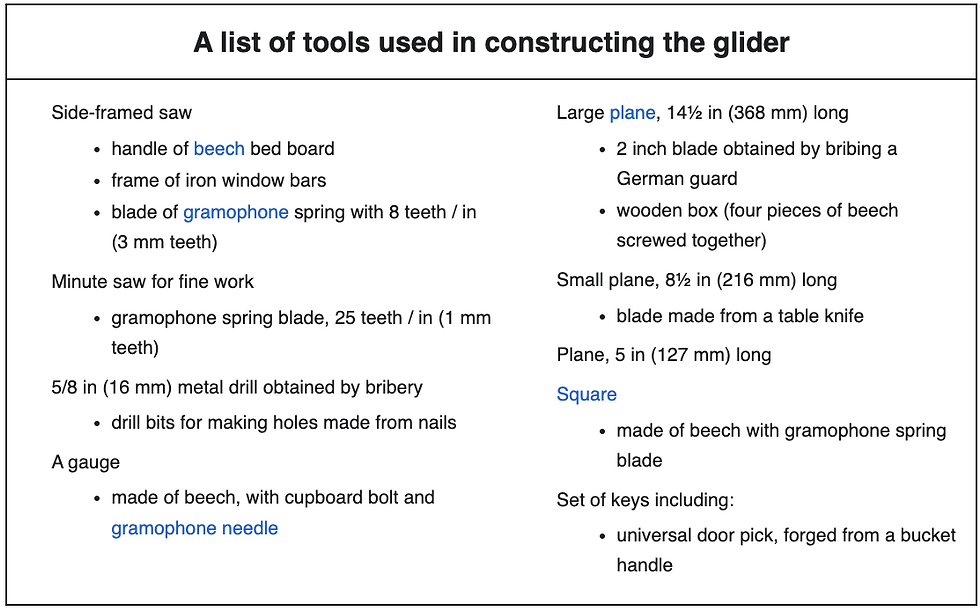

The construction of the glider was a meticulous process, made all the more difficult by the scarcity of suitable materials. The Colditz Cock was constructed primarily from wood, much of which was scavenged or stolen from various parts of the castle. Bed slats were the primary material used for constructing the wing ribs, over thirty of which had to be made by hand. Some ribs served as structural compression elements, vital to the overall integrity of the glider’s wings. The wing spars were fashioned from floorboards, while control cables were made from electrical wiring stripped from unused parts of the castle.

The fabric that covered the glider’s frame was made from prison sleeping bags, which were composed of blue and white checked cotton. This fabric was treated with a homemade version of “dope” to tighten and seal it. The dope was made by boiling millet from German rations, a clever improvisation that allowed the fabric to become taut enough to serve its purpose without compromising the glider’s weight. When completed, the Colditz Cock was a lightweight, high-wing monoplane. It had a wingspan of 32 feet (9.75 metres) and was 19 feet 9 inches (6 metres) in length from nose to tail. The entire structure weighed approximately 240 pounds (109 kilograms), making it a highly efficient design given the limitations of the materials.

The Launch Plan

In addition to the construction of the glider itself, the prisoners devised an innovative launch mechanism. The glider would be positioned on a 60-foot (18-metre) runway, which was to be assembled from tables placed along the chapel roof. To achieve the necessary speed for take-off, the prisoners planned to use a pulley system that would harness the weight of a bathtub filled with concrete. When dropped from a height, this bathtub would pull the glider down the makeshift runway and allow it to reach a launch speed of approximately 30 miles per hour (50 km/h).

The plan was for the glider to be launched during an air raid blackout, which would provide enough confusion and distraction to cover the escape attempt. The goal was to glide the 60 metres across the River Mulde to safety. However, the risks of such an endeavour were considerable. The glider was designed to carry two men, but it was unclear whether it would perform as expected or if it could even stay airborne long enough to cross the river.

The Fate of the Colditz Cock

The construction of the Colditz Cock was nearing completion by the spring of 1945, but by then, the war was almost over. Allied forces were advancing rapidly, and the sound of artillery fire could be heard from the castle. Although the prisoners had initially planned to launch the glider as part of an escape, the changing military situation caused them to reconsider. The British escape officer decided that the glider could be used to send a message to approaching American troops if the SS were to carry out a feared massacre of the prisoners in a last-ditch effort to disrupt the war’s conclusion.

On 16 April 1945, before the glider could be launched, American forces liberated Colditz Castle. The war correspondent Lee Carson, who was embedded with the task force that entered the castle, took the only known photograph of the completed glider in the attic where it had been constructed. While the Colditz Cock never had the opportunity to take flight, the photograph stands as a testament to the resourcefulness of the prisoners.

Post-War Legacy

The Colditz Cock became a symbol of resilience and innovation in the face of adversity, although its post-war history remains somewhat obscure. The castle was situated in the Soviet-controlled zone of Germany after the war, and the glider disappeared during this period. There were no efforts to reclaim it, as the Soviet authorities were not cooperative with such initiatives.

However, the memory of the glider was preserved through the efforts of Bill Goldfinch, who retained his original design drawings. These drawings allowed for the construction of a one-third scale model, which was successfully launched from the roof of Colditz Castle in 1993, nearly fifty years after the original glider had been built.