Texas Ranger Frank Hamer and the Bloody End of Bonnie and Clyde

- dthholland

- Nov 22, 2024

- 8 min read

Frank Hamer's life and career encapsulate the transition from the rough-and-tumble days of the Old West to the more complex, media-driven era of the 20th century. Born in 1884 in Fairview, Wilson County, Texas, Hamer was the son of a blacksmith and the product of a devout Presbyterian upbringing. His father’s workshop was a hub of practical education, and young Frank learned not just the trade of blacksmithing but also the value of hard work and discipline. He was one of five sons, four of whom would become Texas Rangers, marking the family as a cornerstone of Texas law enforcement history.

Hamer grew up on the Welch ranch in San Saba County, where he developed a deep connection to the land and a strong understanding of the natural world. Later, he lived in Oxford, Llano County, now a ghost town, and often joked that he was the only “Oxford-educated Ranger.” Despite his formal education ending after the sixth grade, Hamer displayed remarkable intelligence and a near-eidetic memory. His interests spanned mathematics and history, particularly the legacy of the Texas Rangers and the histories of the Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache tribes. These skills and interests would become vital assets in his later career.

A Natural Lawman

Hamer’s path into law enforcement began in 1905, while working on the Carr Ranch in West Texas. When he captured a horse thief, the local sheriff was so impressed that he recommended Hamer join the Texas Rangers. He enlisted in 1906, starting a career that spanned nearly three decades and cemented his reputation as one of the most skilled and fearless lawmen in the United States.

Hamer’s first assignment was with Captain John H. Rogers’ Company C in Alpine, Texas, where he patrolled the Texas-Mexico border. This was a turbulent region during the Mexican Revolution and the early 20th-century Bandit Wars. Hamer honed his tracking skills on the open prairie and developed a unique ability to interpret human behaviour based on animalistic traits. Criminals, he said, were like coyotes—always looking over their shoulders.

In 1908, Hamer left the Rangers to become the City Marshal of Navasota, Texas, a town notorious for its violence. Shootouts on the main street were so frequent that over 100 men were killed in two years. At just 24, Hamer brought order to the chaos. By 1911, he moved to Houston to work as a special investigator for the mayor and as a deputy sheriff for Harris County, further solidifying his reputation for fearless law enforcement.

A Career Marked by Violence and Controversy

Hamer’s career was as dangerous as it was distinguished. In 1914, he became a deputy sheriff in Kimble County, focusing on livestock theft. The following year, he returned to the Texas Rangers to patrol the South Texas border during the Bandit Wars. Here, he dealt with smugglers, bandits, and unrest spilling over from the Mexican Revolution. During Prohibition, Hamer fought bootleggers, often engaging in deadly shootouts.

In 1917, Hamer married Gladys Johnson, a widow with a turbulent past. Gladys and her brother had been accused of murdering her first husband, Ed Sims. The family’s tensions came to a head when Hamer encountered Gus McMeans, Sims’ brother-in-law, in Sweetwater, Texas. A gunfight erupted, leaving McMeans dead and Hamer wounded. The incident was emblematic of Hamer’s career: swift, violent, and controversial.

Hamer also faced challenges within his profession. In 1918, during an investigation into alleged abuses by the Rangers, State Representative José Tomás Canales accused Hamer of threatening him. Though Canales reported the incident to the governor, Hamer faced no consequences. Despite such controversies, Hamer was credited with saving 15 people from lynch mobs during his career, including leading efforts against the Ku Klux Klan in Texas during the 1920s.

Frank Hamer and the Hunt for Bonnie and Clyde

By 1932, Hamer had retired after nearly 27 years with the Rangers, but his retirement was short-lived. In the early 1930s, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow’s crime spree dominated headlines. Their string of robberies, murders, and prison breaks humiliated law enforcement and captivated the public. The turning point came in January 1934, when the Barrow Gang staged a dramatic prison break at Eastham prison farm, killing a guard and freeing several inmates. Texas prison administrator Lee Simmons, determined to restore the reputation of the prison system, persuaded Frank Hamer to track down Bonnie and Clyde along with the rest of the gang.

Hamer was commissioned as a Texas Highway Patrol officer and seconded to the prison system as a special investigator. Despite the low pay—$180 a month—Hamer agreed, enticed by the promise of a share of the reward money and the right to claim any of the gang’s possessions upon their capture.

Hamer meticulously studied the gang’s movements, noting that they favoured a circular route through Texas, Missouri, and Louisiana, carefully avoiding areas where they might be pursued across state lines. This pattern allowed Hamer to anticipate their moves. "When I began to understand Clyde Barrow’s mind," he said, "I felt that I was making progress."

The Gang's Dallas Shootout

The Dallas County shootout in Iowa is often marked as Bonnie and Clyde’s beginning of their end. Bonnie, Clyde, W.D. Jones, and Buck and Blanche Barrow made their way to Dallas County, Iowa in July 1933.

The gang set up camp in a rural area to lay low after being involved in a shootout in Platte City, Missouri that wounded Buck. Their camp was situated on a hilltop near the Dexfield Amusement Park. Clyde made a few trips into the city of Dexter to buy supplies. The people who serviced him were unaware that he was a notorious outlaw. A nearby resident, Henry Nye, stumbled across their campsite and contacted local authorities. They contacted the Dallas County Sheriff, Clint Knee, who assembled a posse of about 50 people to confront the Barrow Gang.

The posse and gang exchanged gunfire before the gang attempted to escape. One of the vehicles was too damaged by the gunfire to start, and Clyde wrecked a second vehicle they had stolen while attempting to get away. Buck Barrow was injured during the shootout and was left behind. Blanche Barrow was also left behind, but Clyde, Bonnie, and W.D. Jones managed to escape. They traveled on foot until they found a car to steal. After traveling away from Dexter, they wrecked the car, robbed a gas station, and stole another car before they eventually escaped to Sioux City, Iowa.

Buck Barrow died several days after the shootout due to his injuries, and Blanche Barrow was charged and convicted for her involvement with the gang. She served a six-year prison sentence and left her life of crime behind upon her release. W.D. Jones left the gang a few weeks after the shootout but was turned in when his identity was discovered, and spent some time in prison for his involvement with the Barrow Gang. Bonnie and Clyde were both injured in the Dallas County shootout but continued their life on the run for another year.

A Bloody End in Louisiana

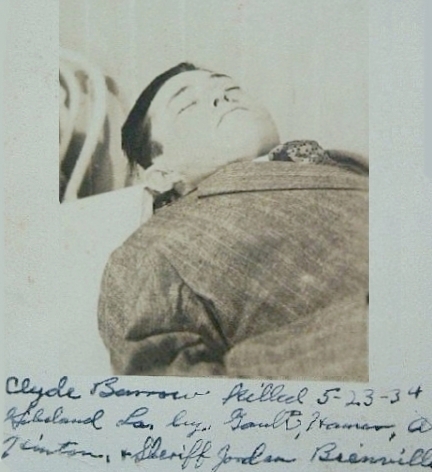

Hamer formed a posse that included Bienville Parish Sheriff Henderson Jordan, his deputy Prentiss Oakley, and fellow former Rangers Maney Gault, Bob Alcorn, and Ted Hinton. The posse tracked the Barrow Gang for months, finally setting up an ambush on a rural road near Gibsland, Louisiana, on May 23, 1934.

At approximately 9:15 am, the posse was still concealed in the bushes and almost ready to give up when they heard a vehicle approaching at high speed. In their official report, they stated they had persuaded Methvin to position his truck on the shoulder of the road that morning. They hoped Barrow would stop to speak with him, putting his vehicle close to the posse's position in the bushes.

The vehicle proved to be the Ford V8 with Barrow at the wheel and he slowed down as hoped. The six lawmen opened fire while the vehicle was still moving. Oakley fired first, probably before any order to do so. Barrow was shot in the head and died instantly from Oakley's first shot and Hinton reported hearing Parker scream.The officers fired about 130 rounds, emptying each of their weapons into the car. The two had survived several bullet wounds over the years in their confrontations with the law. On this day any one of several of Bonnie and Clyde's wounds could have been the cause of death.

According to statements made by Hinton and Alcorn:

Each of us six officers had a shotgun and an automatic rifle and pistols. We opened fire with the automatic rifles. They were emptied before the car got even with us. Then we used shotguns. There was smoke coming from the car, and it looked like it was on fire. After shooting the shotguns, we emptied the pistols at the car, which had passed us and ran into a ditch about 50 yards on down the road. It almost turned over. We kept shooting at the car even after it stopped. We weren't taking any chances.

Film footage taken by one of the deputies immediately after the ambush shows 112 bullet holes in the vehicle, of which around one quarter struck the couple. The official report by parish coroner J. L. Wade listed 17 entrance wounds on Barrow's body and 26 on that of Parker, including several headshots to each and one that had severed Barrow's spinal column. Undertaker C. F. "Boots" Bailey had difficulty embalming the bodies because of all the bullet holes.

The deafened officers inspected the vehicle and discovered an arsenal, including stolen automatic rifles, sawed-off semi-automatic shotguns, assorted handguns, and several thousand rounds of ammunition, along with fifteen sets of license plates from various states. Hamer stated: "I hate to bust the cap on a woman, especially when she was sitting down, however if it wouldn't have been her, it would have been us." Word of the deaths quickly got around when Hamer, Jordan, Oakley, and Hinton drove into town to telephone their bosses. A crowd soon gathered at the spot. Gault and Alcorn were left to guard the bodies, but they lost control of the jostling, curious throng; one woman cut off bloody locks of Parker's hair and pieces from her dress, which were subsequently sold as souvenirs. Hinton returned to find a man trying to cut off Barrow's trigger finger, and was sickened by what was occurring. Arriving at the scene, the coroner reported:

Nearly everyone had begun collecting souvenirs such as shell casings, slivers of glass from the shattered car windows, and bloody pieces of clothing from the garments of Bonnie and Clyde. One eager man had opened his pocket knife, and was reaching into the car to cut off Clyde's left ear.

Hinton enlisted Hamer's help in controlling the "circus-like atmosphere" and they got people away from the car.

The posse towed the Ford, with the dead bodies still inside, to the Conger Furniture Store & Funeral Parlor in downtown Arcadia, Louisiana. Preliminary embalming was done by Bailey in a small preparation room in the back of the furniture store, as it was common for furniture stores and undertakers to share the same space. The population of the northwest Louisiana town reportedly swelled from 2,000 to 12,000 within hours. Curious throngs arrived by train, horseback, carriage, and plane. Beer normally sold for 15 cents a bottle but it jumped to 25 cents, and sandwiches quickly sold out. Henry Barrow identified his son's body, then sat weeping in a rocking chair in the furniture section.

The ambush marked the violent end of one of the most infamous crime sprees in American history. However, the aftermath was tinged with controversy. While the posse had delivered justice, the excessive violence of the ambush drew criticism. Additionally, the promised reward money failed to materialise, leaving each posse member with a meagre $200.23.

A recreation of the shooting, but the footage after the shooting is firsthand and not a recreation

Later Years and Legacy

After the ambush, Hamer continued to work in law enforcement and as a private consultant. He played a minor but notable role in the 1948 U.S. Senate election in Texas, where he confronted armed groups attempting to interfere with ballot tallies. He officially retired in 1949 but remained a legendary figure in Texas history.

Hamer’s life was one of extraordinary resilience and complexity. Wounded 17 times and left for dead on four occasions, he killed between 53 and 70 people over his career. While celebrated for his bravery and effectiveness, he was also criticised for his methods, particularly during incidents like the Sherman Riot and the ambush of Bonnie and Clyde.

Frank Hamer passed away in 1955, two years after suffering a debilitating heat stroke. He was buried in Austin, Texas, near his son Billy, who had been killed during World War II.